The Utopian Megastructure

(this article was written for Milwaukee Tool. You can read the original version on the company’s blog.)

In his 2010 piece for the New Left Review entitled “Who Will Build the Ark?”, writer and urban theorist Mike Davis posited an intriguing thesis as a counterweight to the bleak climate science of our time: that cities are paradoxically both one of the primary causes of climate change and one of the best shots that humanity has at surviving it.

Grappling with the immense problem of a rapidly changing planet, Davis proposed a commensurately massive and radical solution:

“…a new ark,” he wrote, “will have to be constructed out of the materials that a desperate humanity finds at hand in insurgent communities, pirate technologies, bootlegged media, rebel science and forgotten utopias.”

If you were to go looking for forgotten utopias, a good place to start would be the notebooks and manifestos of a handful of avant garde architects who worked during the culturally and politically tumultuous period of the 1960s and 70s. Among their esoteric writings you would find peculiar sketches of colossal constructs and massive modular formations that—while diverse in their shape, appearance, and philosophy—share a common name: megastructures.

Given their immense scale and the soaring ideals that undergird them, megastructures cannot help but lean towards utopia like so many teetering towers of Babel. Their gravity can be felt in popular culture and every strain of modern architecture, yet few were ever actually built. Like utopia, most megastructures exist—as science-fiction writer Ursula K. LeGuin once put it while meditating on the concept—merely as “blueprints of the head.”

But “every utopia,” she warned “…has been both a good place and a bad one.”

This piece will explore some of history’s forgotten utopian megastructures, attempt to answer the question of why they didn’t catch on, and follow their lumbering tracks through the collective imagination into the uncertain future of a rapidly changing world.

What is a megastructure?

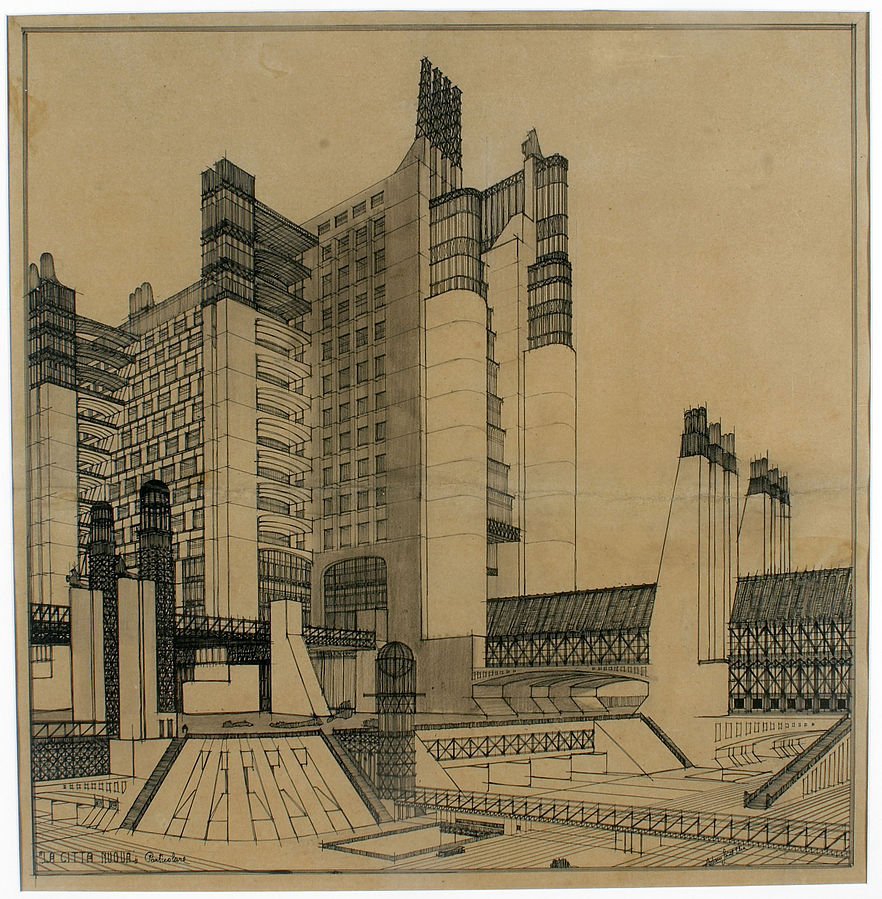

It’s difficult to pin down a single definition and it depends on who you ask, but for our purposes, a simple explanation is that a megastructure is a whole city inside a building. While primarily associated with fictional depictions in popular media, the idea of titanic multi-purpose enclosures that house entire metropolises actually sprang from the minds of real-world architects and urban theorists. Early traces of megastructures can be glimpsed in the works of Le Corbusier, Antonio Sant’Elia, and the feverish drawings of Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Although not part of a cohesive movement, the various megastructural architects of the 60s and 70s shared in the conviction that their monumental creations could change the world for the better.

The influence of Buckminster Fuller

Of all the names associated with megastructures, Buckminster Fuller is perhaps the most familiar. Born on July 12, 1895, Fuller was a pioneering American architect, inventor, teacher, poet, and urban theorist. A freewheeling eccentric who pushed against the grain of institutional thought, he had 28 patents to his name, wrote more than two-dozen books, and received almost 50 honorary degrees throughout his lifetime. Fuller’s intellectual playfulness, deep concern for the environment, and compassion for society’s downtrodden made him an appealing figure to members of the 1960s counterculture who were fed up with the consumerism and nuclear militarization of the cold war era. Activists, hippies, and disaffected youth devoured his writings on “comprehensive design” and aspired to the sustainable futuristic lifestyle epitomized by his signature creation: the geodesic dome.

A compressed tensile lattice of interconnected triangles makes up the skeleton of the geometrically curved or “geodesic” dome, whose surface can then be composed from a variety of materials. Some of the earliest versions were made of aluminum tubing and a skin of plastic stretched over the frame. Geodesic domes are lightweight yet incredibly strong and provide a great deal of open interior space. They’re also inexpensive and fairly easy to assemble.

Geodesic domes are unique in comparison to some of the other designs discussed in this piece in that quite a few of them actually got built. Today, there are roughly 300,000 geodesic domes in existence, according to the Buckminster Fuller Institute. The majority of them are small single family-residences but a noteworthy few were tremendous in scale, including the 206 ft wide 250 ft tall Biosphere Environment Museum erected during the famous Expo 67 in Montreal, Canada. Another recognizable example is the gigantic geodesic dome featured at Disney World’s Epcot Center, which draws its name from Fuller’s environmental writings about “Spaceship Earth.” Ever prone to wild flights of imagination, Fuller at one point proposed that a massive geodesic dome be dropped over the island of Manhattan. He even envisioned a flying city of interconnected spheres called the Spherical Tensegrity Atmospheric Research Station (STARS), otherwise known as Cloud 9. However, like the most magnificent of the megastructuralist dreams, neither was ever built.

Fuller was influential in his belief that society had arrived at a point where we could design self-sustaining structures that preserved nature while also providing for the needs of every single person on Earth. It’s a belief that was shared by a handful of others who around the same time were busily drawing up the blueprints for megastructures of their own.

Metabolism: the living city

Meanwhile in Japan, a small cadre of activist architects were laying the conceptual foundations of a revolutionary new kind of high-density modular architecture inspired by the laws of biology. They called it “Metabolism”.

The Metabolism movement sprouted amid the uncertainty and gloom of a defeated post-World War II Japan. It was in the long shadows of the mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki that a handful of architects began to radically reimagine the city of a brighter tomorrow.

“I found it meaningless to attempt to revive an already destroyed city by means of a monument,” Metabolist architect Kisho Kurokawa once wrote. “I felt that it was important to let the destroyed be and to create a new Japan.”

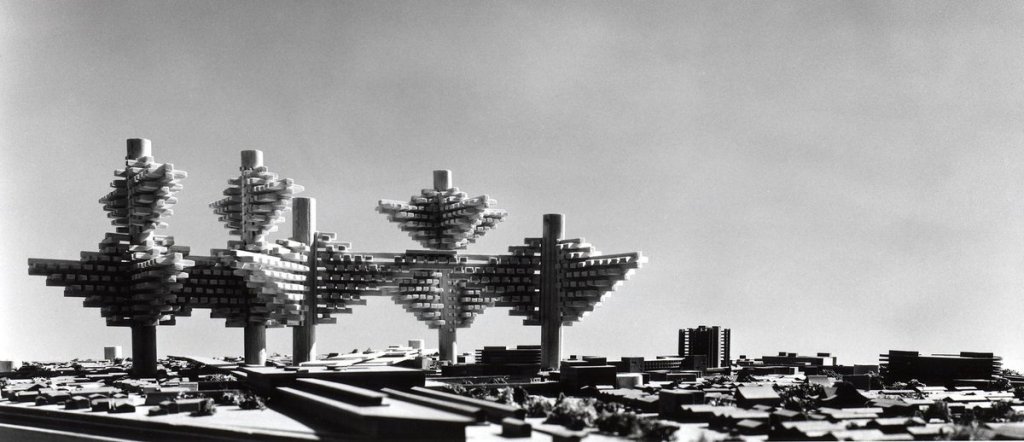

Led by Kenzo Tange, the Metabolists released their formative manifesto at the 1960 World Design Conference in Tokyo. They believed they could use architecture as a tool to elevate democracy and human progress in the midst of a dangerous world. Deriving their name (shinchintaisha 新陳代謝) from natural metabolic processes, the Metabolists thought of cities as massive living things capable of adaptation and growth. Much as an organism replaces its worn out cells with new ones, the Metabolists imagined gigantic structures that could expand according to their own interior logic and react defensively to cataclysmic changes in their surrounding environments. A typical Metabolist megastructure would resemble an immense steel tree festooned with “cells” or individual modules that could be clipped on or removed as their overseers saw fit.

In their time, the Metabolists generated a number of awe inspiring megastructural concepts, including Tange’s eighteen mile long floating city for Tokyo Bay, Helix City modeled off the spiraling structure of DNA, and Arata Isozaki’s City in the Air.

Their utopian leanings were eventually swept away however as the world continued to change around them. Since its construction in 1972, the Nakagin Capsule Tower in Ginza has stood for decades as one of the sole remaining monuments to Metabolism’s lofty ideal of modularity. Composed of 140 capsule apartments, the iconic 14 story tower has fallen into disrepair over the years and is in danger of being dismantled.

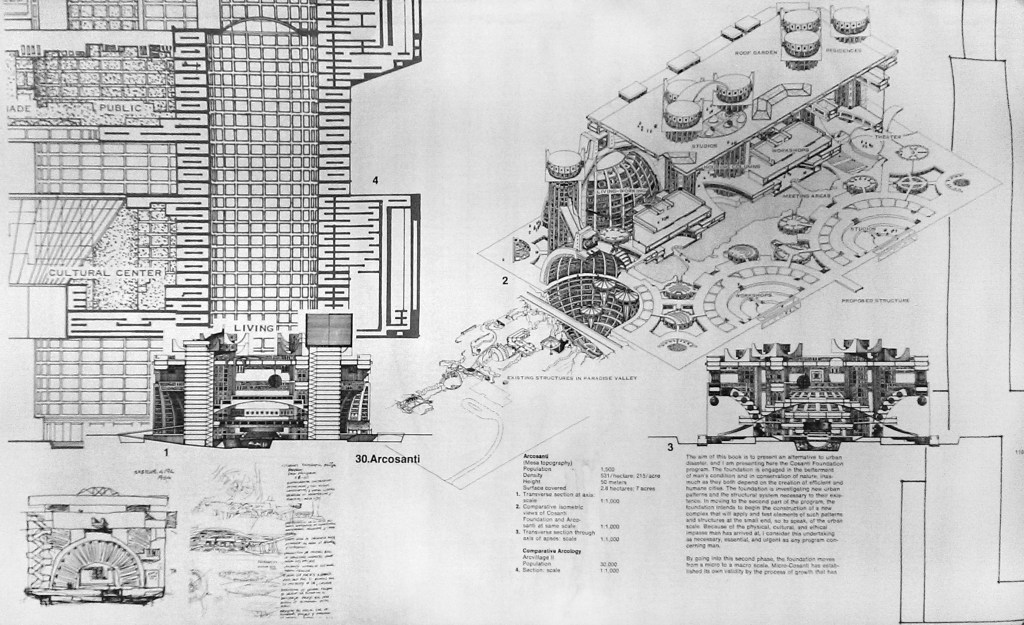

Arcology: the city and nature in harmony

We come now to the granddaddy king of the megastructure, the “prophet in the desert” himself: Paolo Soleri.

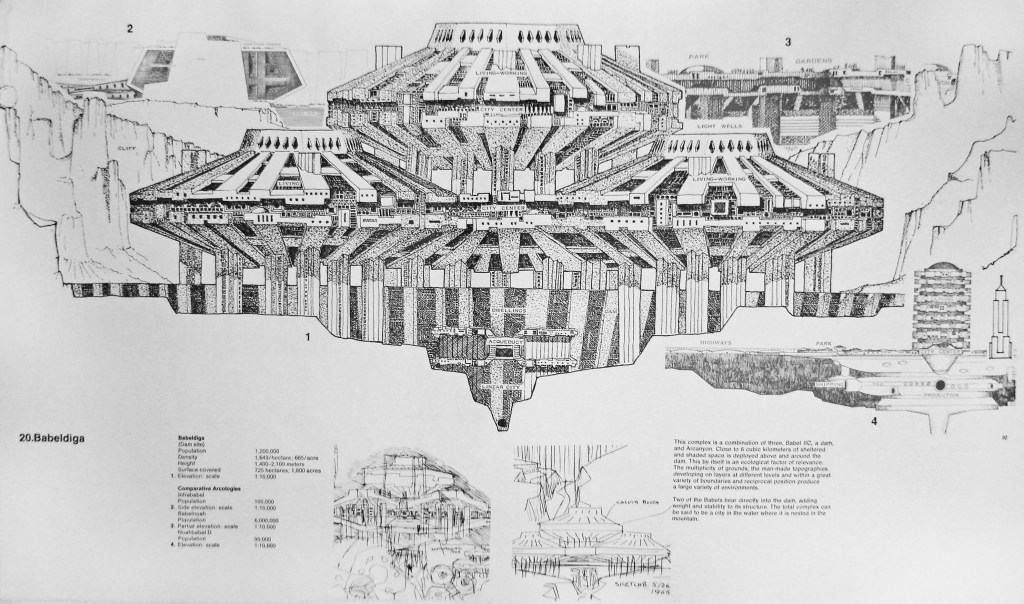

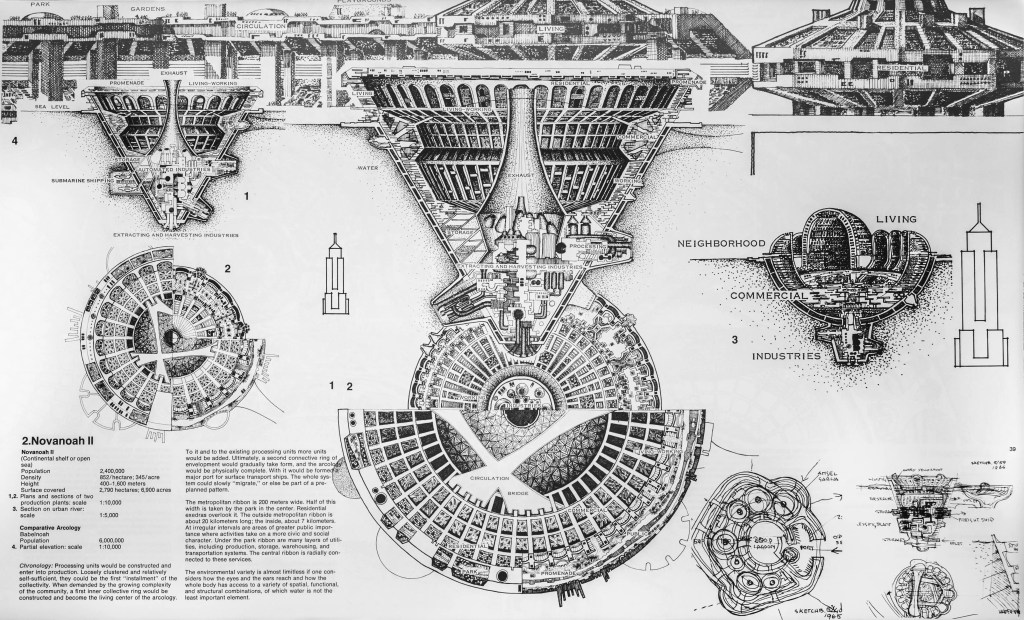

Born in Turin, Italy on June 21, 1919, Soleri was a visionary architect and philosopher known primarily as the inventor of Arcology. A portmanteau of “architecture” and “ecology”, arcologies are eco-friendly megastructures designed for the express purpose of minimizing humanity’s impact on the natural world.

A student of Frank Lloyd Wright and the environmentalist movement of the 60s, Soleri argued that modern cities are designed less for humans and more for cars. The result is the opposite of arcology: bloated, inefficient, environmentally destructive urban wastelands sprawling ever outward across a flat horizon. If left unchecked, Soleri warned, modern practices of urbanization would someday pose a direct threat to all life on Earth.

Soleri positioned his utopian arcology as an urgent alternative to the dystopian landscapes of suburbia, megalopolises, and even ecumenopolises on the farthest end of the theoretical spectrum. We are all well acquainted with suburbia—the sprawling mixed-use residential areas that surround cities—but these other terms are perhaps less familiar.

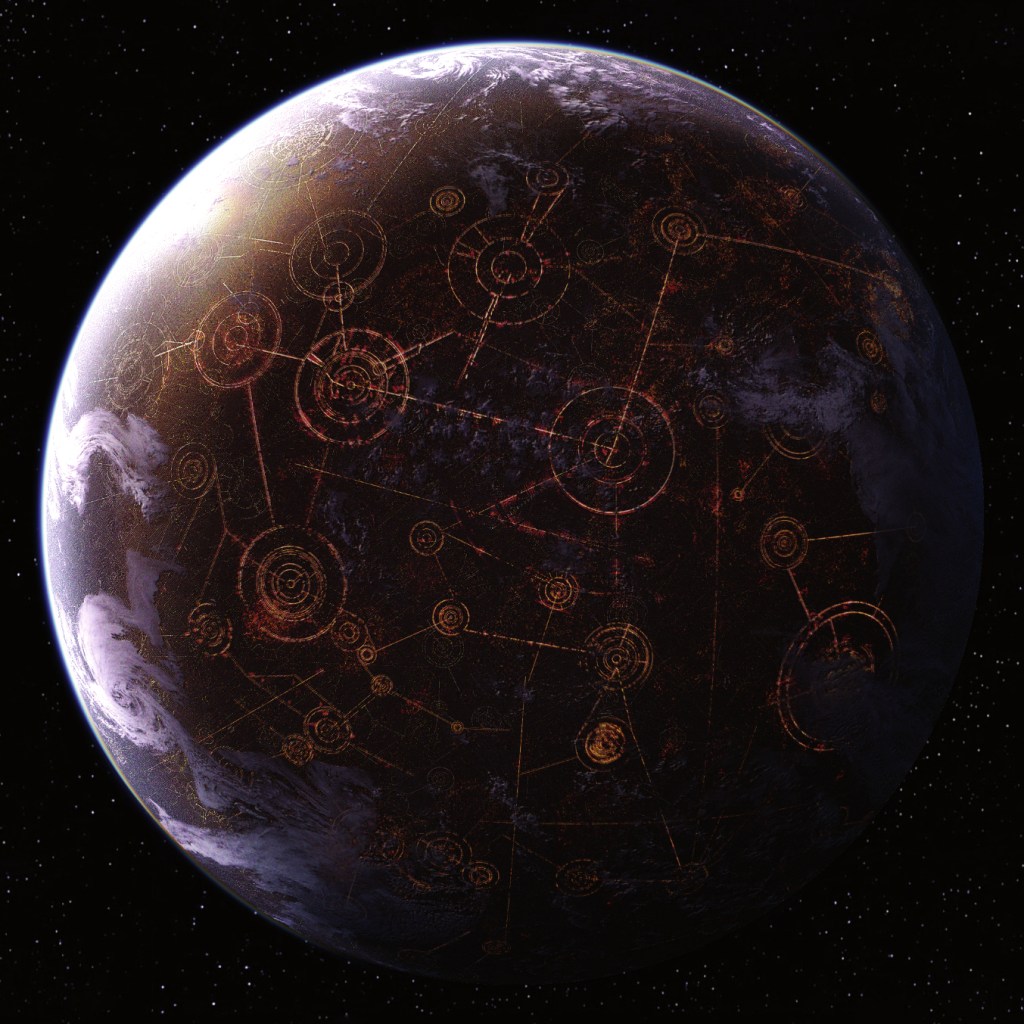

Megalopolises are gigantic “mega cities” or clusters of cities with populations numbering in the tens of millions that spread across a vast region. Like arcologies themselves, this might sound like science-fiction but several megalopolises already exist, particularly in North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa. Two prime examples are “BosWash” in the northeast and “SoCal”, the enormous interconnected urban region stretching hundreds of miles between Los Angeles and San Diego in Southern California. An ecumenopolis is the next logical extreme: a city that covers an entire planet. Like arcologies, none of these of course actually exist—yet. If you’re a fan of Star Wars, you’ve actually already seen one depicted on the planet Coruscant, which itself is modeled off of the imperial capital world of Trantor in Isaac Asimov’s seminal Foundation Trilogy.

This kind of planet devouring urbanization is exactly what Soleri wanted to avoid. Similar to the Metabolists in Japan, he talked about his sustainable megastructures as “hyperorganisms” brimming with transcendent potential. Instead of building out along a horizontal plane, the firebrand Italian architect insisted that we should build up into three dimensional space. Though themselves gigantic in stature, miniaturization actually lay at the heart of Soleri’s arcologies. He compared them to passenger ships (or arks) that contain entire cities within their compact frames, complete with everything necessary for human life: food, water, shelter, education, healthcare, entertainment, transportation networks, and the commons—all compressed into a single self-sufficient package. The car would become obsolete, as everything inside an arcology would be integratively designed to be within walking or biking distance. If needed, a person could spend their entire life in an arcology and never once have to step outside.

Meanwhile, beyond the arcology’s towering walls and vaulted apses, nature in all its vastness would be left alone to heal itself. Humanity would once again, Soleri dreamt, be “surrounded by uncluttered and open landscape.”

“The compactness of arcology gives back to farming and to land conservation 90 percent or more of the land that megalopolis and suburbia are engulfing in their sprawl,” he wrote. “To be a city dweller and a country man at one and the same time, to be able to partake fully of both city and country life, will make the arcology a place in which man will want to live.”

Soleri died of natural causes at his home in Paradise Valley, AZ on April 9, 2013. He left behind dozens of stunning arcology designs in his book Arcology: the City in the Image of Man. None were ever built. The closest he came was Arcosanti. Crouched along a dried up riverbed in the Sonoran Desert 90 minutes outside the sprawling city of Phoenix, AZ, Arocsanti is a prototype arcology whose transient inhabitants have kept the flame of their founder’s unique architectural vision alive for the last 50 years and running. Begun in 1970, the earth-cast “urban laboratory” remains only 5 percent completed to this day.

Archigram: the technological city

Our final entry in the megastructural canon—there are many others that go unmentioned here—burst on the scene in 1961 with the first pressing of a strange magazine called Archigram. In its pages, avante garde architects Warren Chalk, Peter Cook, Dennis Crompton, David Greene, Ron Herron, and Michael Webb railed against the dullness and conservatism of modern architecture. Hungry for fresh alternatives, they decided to follow in the footsteps of their hero Buckminster Fuller and began sketching exciting new cityscapes with madhatter megastructures at their heart.

Their provocative designs were riots of color and complexity that leapt off the page with a cartoonish flair. While much was made of their irreverent humor, the Archigramists made it clear that they weren’t just kidding around.

“A lot of our projects are highly serious and a lot of built buildings are a bad joke,” Archigramist Peter Cook once said in a 1970 interview.

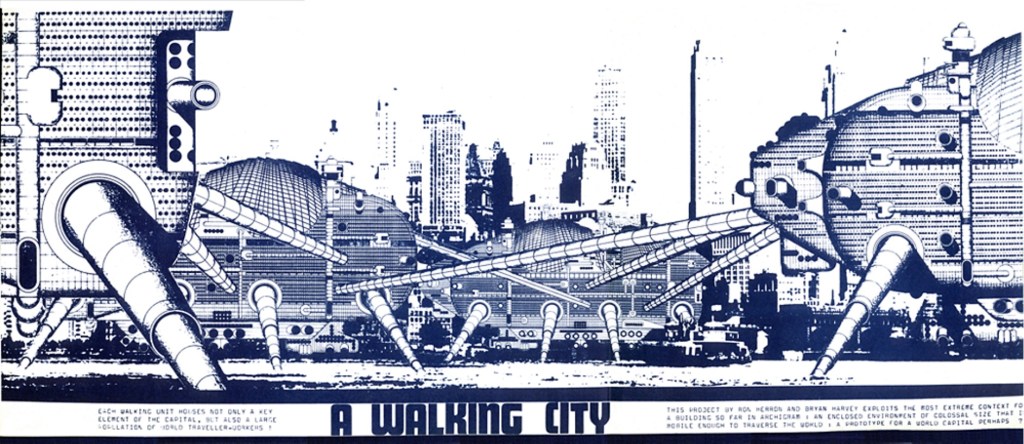

One of their most quintessential creations was Cook’s “Plug-In City”. Bracketed by permanent cranes, its design revealed that, like their Metabolist contemporaries in Japan, the Archigramists had an affinity for modular megastructures composed of interchangeable parts. In an echo of the capsules of Kurokawa’s Nakagin Tower, prefabricated housing units could be added or subtracted as needed to Plug-In City’s massive honeycombed frame. Each unit would be designed by the occupant, allowing for a great deal of variety in living spaces. Another radical proposal came from Herron, who imagined a “Walking City” that could crawl across the land or float through waterways.

As Simon Sadler puts it in his book Archigram: Architecture without Architecture, one of the primary aims of the Archigramists was “to bring architecture up to speed with leading, artistic, technological, and cultural tendencies—‘pop’ influences in particular.” Archigram is distinct from the other utopian megastructural schools of thought in that, as Sadler states, its practitioners were largely unconcerned with the health of the natural world. Nor were they particularly interested in architecture as a tool for uplifting society’s downtrodden masses. Their philosophy instead called for the harnessing of technology and the bounties of private industry to further the cause of individual freedom and expression. Archigram is remembered less for what it actually built and more for the rebellious style of its eye-popping urban designs.

The fall of the megastructure

There were many factors that contributed to the decline of the megastructure. For one thing, there’s the practical matter that projects of such immense scale are extremely expensive to build and would likely take many years to complete. What’s more, for all their effervescent writings and breathtaking designs, Soleri and his contemporaries were often light on details about how exactly their grand visions would work in the real world. Their naivety and failure to reckon more directly with the overarching political and cultural forces of history also played a hand in their consignment to obscurity. In his piece “The Tragedy of the Megastructure”, French architect Valentin Bourdon portrays the movement’s downfall in part as a matter of changing belief systems. The values of environmentalism, inclusive space, and cohabitation that once stood at the heart of the megastructure fell out of vogue and were eventually replaced, like so many Archigramist pods, with market driven concerns of commercialism and profit. Instead of being dismantled altogether, the idyllic concept of the megastructure was broken down and repurposed in the form of “big-buildings” like shopping malls and housing projects that conformed with rather than reimagined the modern urban paradigm. With Soleri as a near solitary holdout, many of the once starry-eyed architects of the 60s and 70s abandoned their blueprints of a better future and simply moved on with their careers.

How the megastructure lives on

In his book Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past, architecture historian Reyner Banham describes his subjects as “dinosaurs” and “monumental follies”, a “whitening skeleton on the dark horizon of our recent architectural past”.

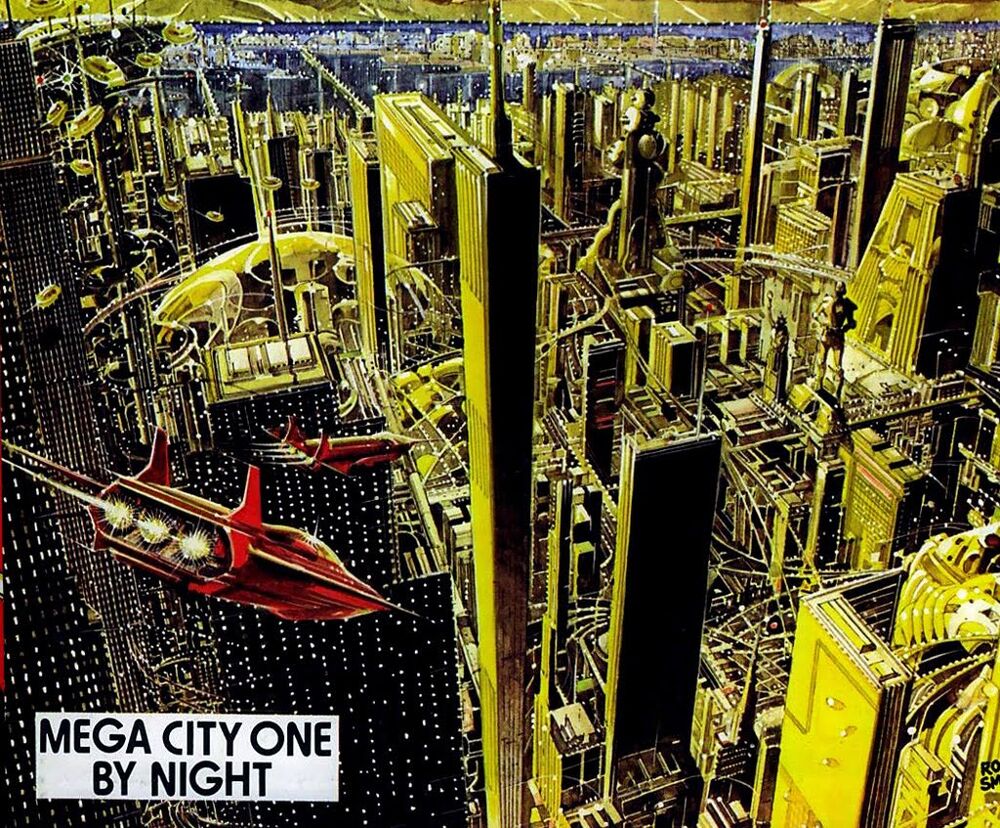

Megastructures did indeed fade back into the landscape but Banham’s reports of their total irrelevance are greatly exaggerated. They live on to this day, primarily in science-fiction literature, comics, cinema, and videogames; albeit mostly as emblems of techno-dystopia, their original radiance cast into shadow. You can glimpse their hulking corporatist forms in the cyberpunk novels of William Gibson, Ridley Scott’s Bladerunner, and Katsuhiro Otomo’s groundbreaking anime Akira. Familiar to some from their appearance in Sim City, dark versions of Soleri’s arcologies can also be explored in more recent videogames like Ascent and Ghostrunner. Notably, the Bioshock franchise features its own airborne and underwater megastructures erected as monumental havens of individual freedom that have since transformed into nightmarish playgrounds of violence and madness.

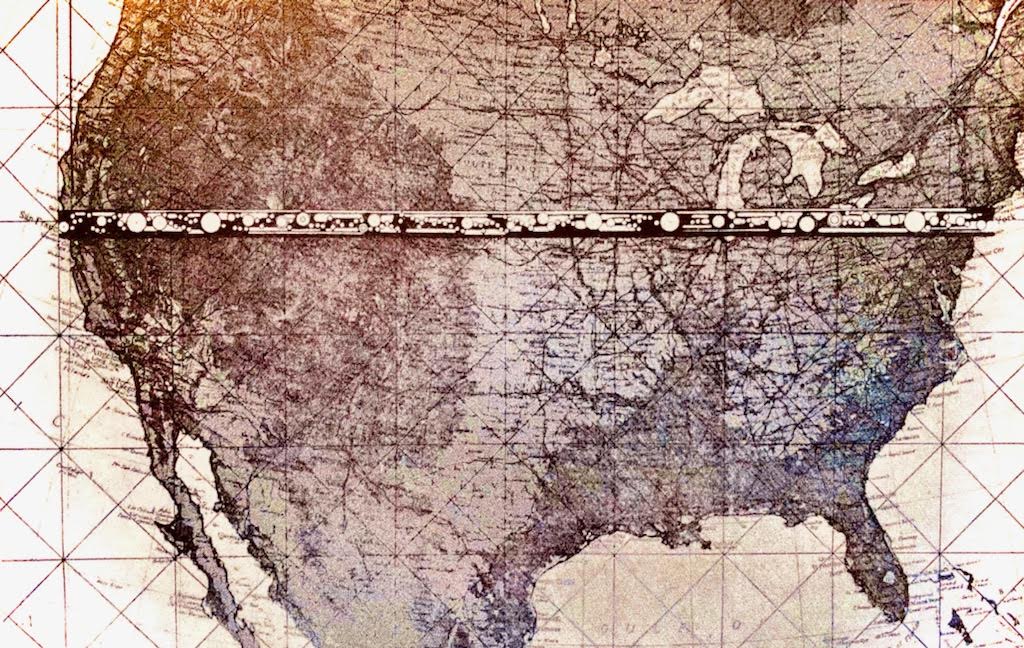

Short of vanishing from the real-world altogether, Banham would probably be shocked to learn that megastructures have actually re-emerged over the last two decades as viable urban concepts. The proposed durable pyramid of the New Orleans Arcology Habitat (NOAH) was a response to the destruction of Hurricane Katrina in the early 2000s. More recently, former Wal-Mart executive Marc Lore has unveiled plans to build a $400 billion Rapture-esque luxury city called Telosa somewhere in the American southwest. Meanwhile, Saudi Prince Mohammed Bin Salman has proposed NEOM, a project reminiscent of the Archigramist’s linear concept of a “Comprehensive City”. The controversial $550 billion automated megalopolis would have flying cars, its own moon, and would stretch in a straight unbroken line across 170 kilometers of the Saudi Arabian desert.

At their best, megastructures are beautiful Edenic bastions of democratic thought that prioritize the public good and the sanctity of the natural world. At their worst, they are entombed authoritarian police states that systematically degrade human dignity and stripmine the environment of its ever diminishing resources. The post-apocalyptic film Dredd (2012) based on the Judge Dredd comic series contains perhaps the most vivid summation of the zone that megastructures currently occupy in the popular imagination:

“America is an irradiated wasteland. Within it lies a city. Outside the boundary walls, a desert. A cursed earth. Inside the walls, a cursed city, stretching from Boston to Washington D.C. An unbroken concrete landscape. 800 million people living in the ruin of the old world and the megastructures of the new one. Mega blocks. Mega highways. Mega City One.”

Mega City One is based on a real place. The so-called “BosWash” region “stretching from Boston to Washington D.C.” is the planet’s largest megalopolis currently in existence. Covering an area of almost 450 miles, it contains 50 million people and has an economy larger than the United Kingdom’s. Rocketing down BosWash’s mega-highways in the cursed future timeline of the Dredd-verse, one can spy through the smog perhaps the darkest vision of the megastructure: Absorbed into the Mega City, its sprawl banishing destiny is forgotten.

And yet.

It’s impossible to deny the exhilaration one feels when pouring over the schematics of megastructures from a more optimistic yesterday. What would it be like to live, work, and play in such radically reimagined built environments? Questions like this, if framed correctly and treated with delicate care, can spur us in the direction of more egalitarian and ecologically harmonious alternatives to our current way of life.

For her part, Le Guin believed we needed to re-imagine the idea of utopia itself in the spirit of “impermanence and imperfection, a patience with uncertainty and the makeshift, a friendship with water, darkness, and the earth.”

In the age of climate change, the need to preserve the natural world and save people from disaster is once again being felt as an urgent imperative. Are megastructures the arks that will carry us to a more sustainable future? Or merely the fallen escapist fantasies of egocentric elites? One thing’s for sure: There is no silver bullet. Megastructures themselves may not be the key, but the utopian idealism and unfettered imaginativeness that originally birthed them ought to be striven toward if we dare hope to transcend the dystopian crises of our time.

![Red-eyed_Tree_Frog_(Agalychnis_callidryas)_3[1]](https://redshiftblues.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/red-eyed_tree_frog_agalychnis_callidryas_31.jpg?w=1024)

![Falcon_Heavy_Demo_Mission_(40126461851)_-_cropped[1]](https://redshiftblues.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/falcon_heavy_demo_mission_40126461851_-_cropped1.jpg)

![TheThreeStigmataOfPalmerEldritch(1stEd)[1]](https://redshiftblues.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/thethreestigmataofpalmereldritch1sted1.jpg)

![pkdwithcat[1]](https://redshiftblues.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/pkdwithcat1.jpg)

Ricky getting shot in the head cut my career at Yellow Cab short. That and the lies about money.

Ricky getting shot in the head cut my career at Yellow Cab short. That and the lies about money.